Induced Forests in Planar Graphs

There is an old conjecture that every $n$-vertex planar graph contains an induced forest on at least $n/2$ vertices.

The best lower bound is due to Borodin, who shows that every planar graph has an acyclic 5-colouring, so each cycle in the graph receives at least three colours. This means that the two largest colour classes have size at least $2n/5$ and induce a forest (a graph with no cycles). Borodin’s proof is a long argument by minimum counterexample that has considerable case analysis.

Attack by tripod decomposition

In January 2021, I spent some time thinking about tackling this problem using a tripod decomposition. In particular, the original tripod decomposition of Pilipczuk and Siebertz that differs in the way the way the tripod legs are chosen (each leg is a shortest path to the outer cycle).

The graph induced by the three legs of this kind of tripod is highly structured. It has a layering with at most three vertices per layer. In fact, the lower bound graph of Akiyama and Watanabe has this structure, in which the winding path is an induced path of length $\lceil n/2\rceil$.

Define a tripod graph as a planar graph that has a layering with at most $3$ vertices per layer.

Lemma: For any tripod graph $G$, there exists a partition $(A,B)$ of $V(G)$ such that $G[A]$ and $G[B]$ are forests.

Proof: We may assume that $G$ has exactly three vertices per layer and that it is edge maximal. Let $L_1,\ldots,L_\ell$ be the layering of $G$ and let $x$, $y$, and $z$ denote the three vertices of $L_1$. We will actually prove something stronger: There exists two partitions of $(A’,B’)$ and $(A’‘,B’’)$ satisfying the conditions of the lemma and such that $x,y\in A’$, $x\in A’’$, and $y\in B’’$. The proof is by induction on $\ell$.

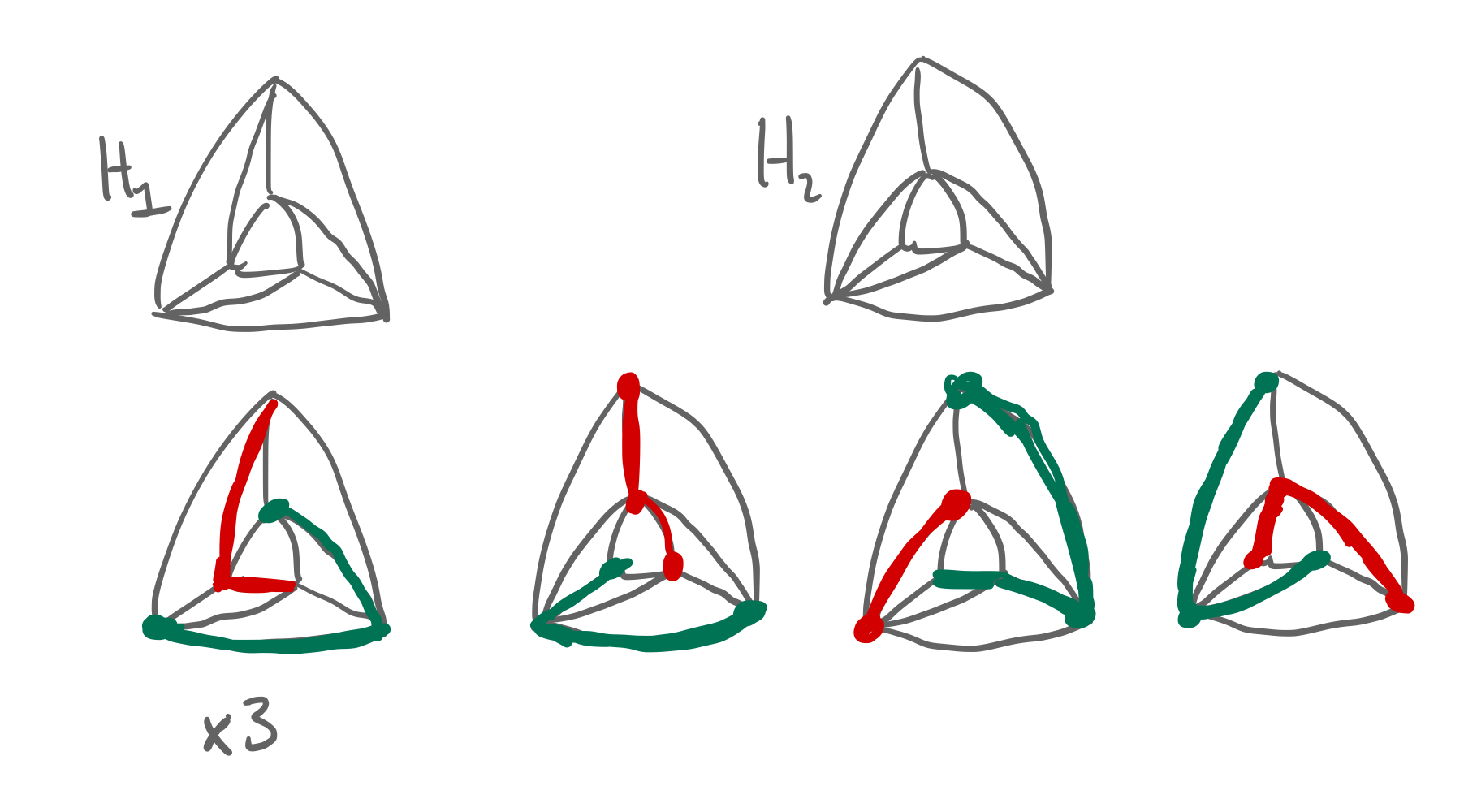

Consider the 6-vertex graph $G_{12}:=G[L_1\cup L_2]$. Up to symmetry, there are only two graphs: $H_1$ that has rotational symmetry and $H_2$ that does not. This picture shows how, in either case, to partition $V(G_1)$ into $(A’,B’)$ and $(A’‘,B’’)$.

Let $x’$, $y’$, and $z’$ be the vertices of $L_2$. Depending on which of the partitions we use for $G_{12}$, we either have $x’$ and $y’$ in the same set or in different sets. In either case, the inductive hypothesis says that we can partition the vertices of $G_{\ge 2}:=G[L_2\cup\cdots\cup L_\ell])$ into sets $(A_2,B_2)$ with $x’$ and $y’$ in the same or different sets (as appropriate) and so that each of $G_{\ge 2}[A_2]$ and $G_{\ge 2}[B_2]$ is a forest. Combining and renaming gives us a partition $(A,B)$ of $V(G)$. To see that $G[A]$ is a forest, observe that $G_{12}[A]$ contains no cycles, by construction and $G_{\ge 2}[A]$ contains no cycles, by induction. The only remaining possibility is a cycle $C$ that contains vertices $L_1$ and vertices in $L_3$. Such a cycle $C$ would contain two vertices of $L_2$ and therefore contains an edge of $L_2$. Thus, $C$ contains a chord and the shortest cycle in $G[V(C)]$ is a cycle in $G_{12}$ or a cycle in $G_{\le 2}$. ∎

Note that the preceding lemma implies that $G$ is $4$-colourable since each of $G[A]$ and $G[B]$ is a tree, and therefore bipartite.

By discarding the feet of a tripod $Y$, the preceding lemma implies that $Y$ contains an induced forest of size at least $(|Y|-3)/2$ that is not adjacent to the cycle in $G$ that defines the tripod $Y$. This means that, for a tripod partition $\mathcal{P}$ of $G$, $V(G)$ has a partition into three sets $(A,B,X)$ such that $G[A]$ and $G[B]$ are each forests and $|X|\le 3|\mathcal{P}|$. Thus, $G$ contains an induced forest of size at least $n/2 - 3|\mathcal{P}|/2$. By working directly with small cases, we might be able to do better.

Maybe we can strengthen the preceding lemma so that, for a tripod $Y$, we obtain a partition $(A,B)$ such that $(A,B)$ partitions each inner face of $G[Y]$ into two paths. I think this is only a matter of a bit more case analysis on $G_{12}$. [I think I’ve mostly figured this out by studying which of the two tracks contain the same-coloured vertices—we only need to change the color there if there is an inter-track edge, which seals off the other colour.]

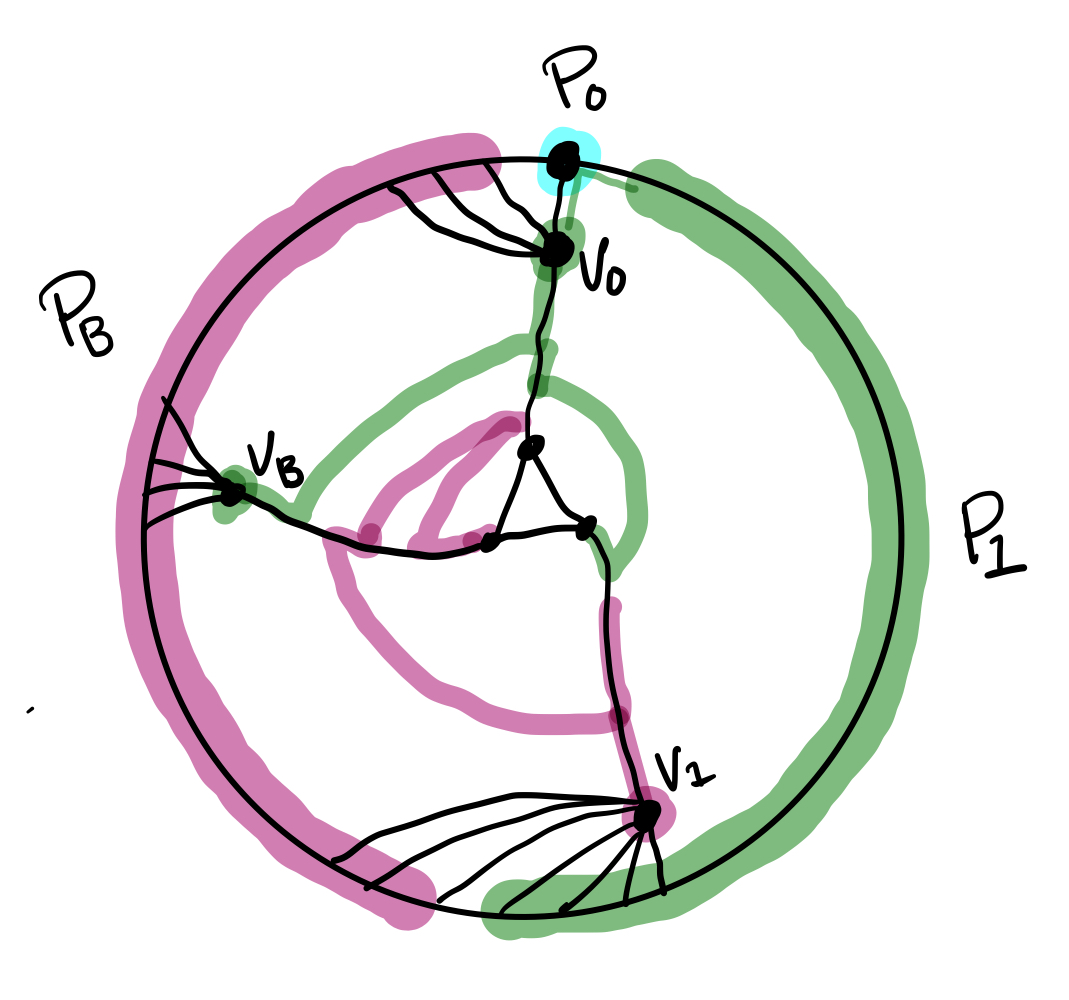

Now we have some control over how the tripod $Y$ interacts with the cycle $F$ that surrounds it. In particular, it looks like our subproblem is a cycle $F$ in $G$ that is partitioned into two paths $P_A$ and $P_B$ by $A$ and $B$. One of these paths, say $P_A$ has at least two vertices and We can split $P_A$ into a single-vertex path $P_0$ and a the remaining path $P_1$. Now we can look for a tripod with the parittion of $F$ given by $(P_0,P_1,P_B)$. This means each vertex in the interior of $A$ has to choose a shortest path to $F$. In the case of ties we prefer $P_1$, followed by $P_0$, followed by $P_B$. Assume this gives us a tripod $Y$ of size at least $3$. Because of the tie-breaking rules, $Y$ has

- a foot $v_B$ adjacent to $P_B$ and not adjacent to $P_1$ or $P_0$;

- a foot $v_0$ adjacent to $P_0$ and not adjacent to $P_1$ (so $v_0$ is adjacent to a single vertex of $A$); and

- a foot $v_1$ adjacent to $P_1$ (and possibly adjacent to $P_0$ and/or $P_B$)

Now apply the lemma above with $v_B\in A$ and $v_0,v_1\in B$ (Note that the tie-breaking rules eliminate some cases in the proof of the lemma.) This lets us keep everything except $v_1$, which may be adjacent to two or more vertices of $P_B$ and adjacent to two or more vertices of $P_A$. In this case, I’m not sure what to do with $v_1$ other than put it in some excluded set $X$.

Unfortunately, the only obvious upper bound on the size of $X$ is $(3n-6)/4$. Maybe we could be a bit more clever and get $|X|\le n/2$, but we won’t do better than that because of the following example: Take a square grid $G_0$ and put a degree-4 vertex inside each face. Then approximately half the vertices are degree-4 and we could imagine that the algorithm ran for a while and put all of the vertices of $G_0$ into $A$ and $B$ in which a way that each face of $G_0$ has two vertices from each of $A$ and $B$. Then all the remaining degree-4 vertices have to go in the exceptional set $X$. In this case we only get two spanning trees containing a total of$ \approx n/2$ vertices. (The same example works if we start with a hexagonal grid.) This case might be worth studying. Maybe there’s a good explanation for why the algorithm wouldn’t produce sets $A$ and $B$ this way. To do better than Borodin’s bound, we need $|X|<n/5$.

In general, it’s the small cases like this that are the killers, so there will be small cases to deal with. For example, when $F$ contains only one vertex $v$ in its interior. If $F$ is a 3-cycle, then this is easy because we can add $v$ to the forest with only one vertex in $F$. For $|C|\ge 4$, there is the possibility that $v$ can’t go into either tree. To deal with this, we would have to make sure that small cycles containing only a single vertex consist of a monochromatic path and a

4-Connected triangulations

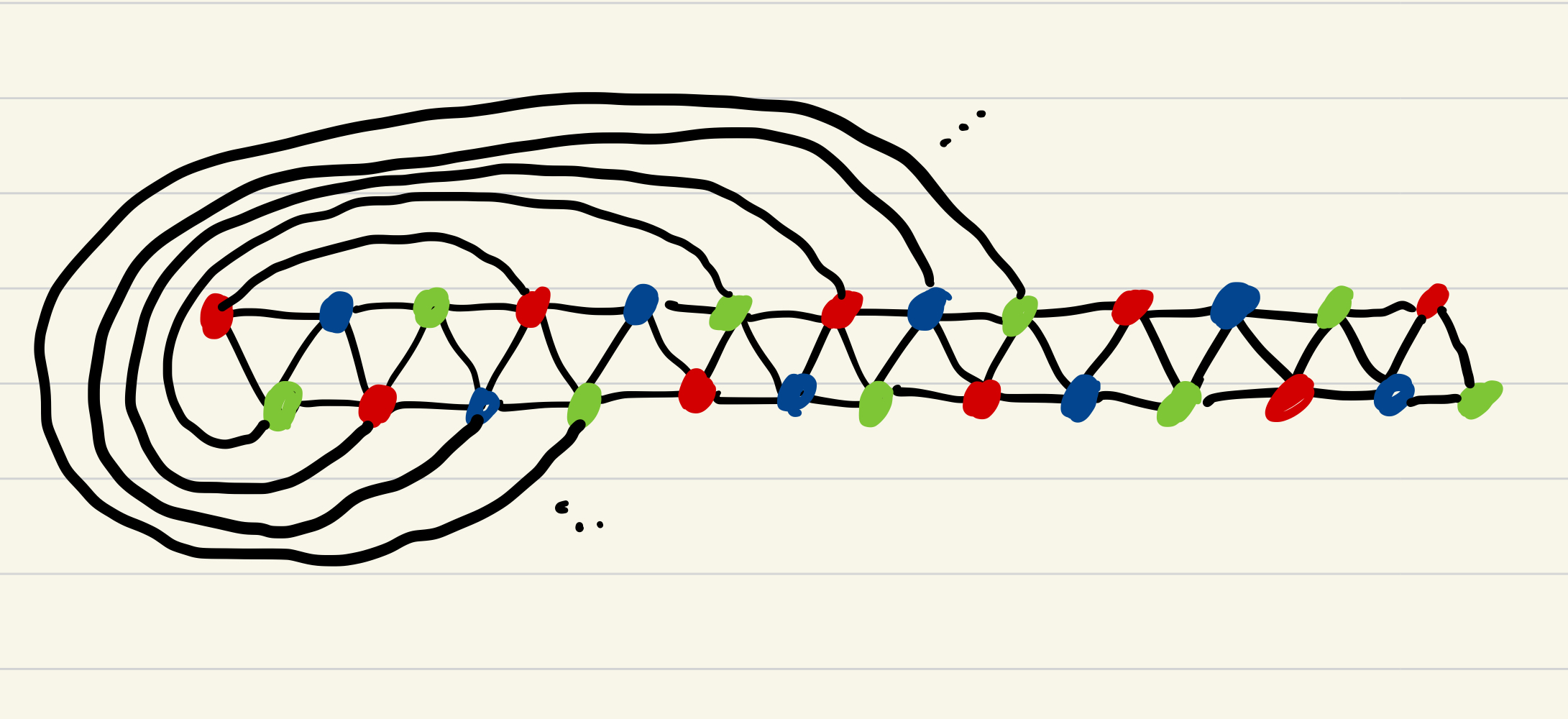

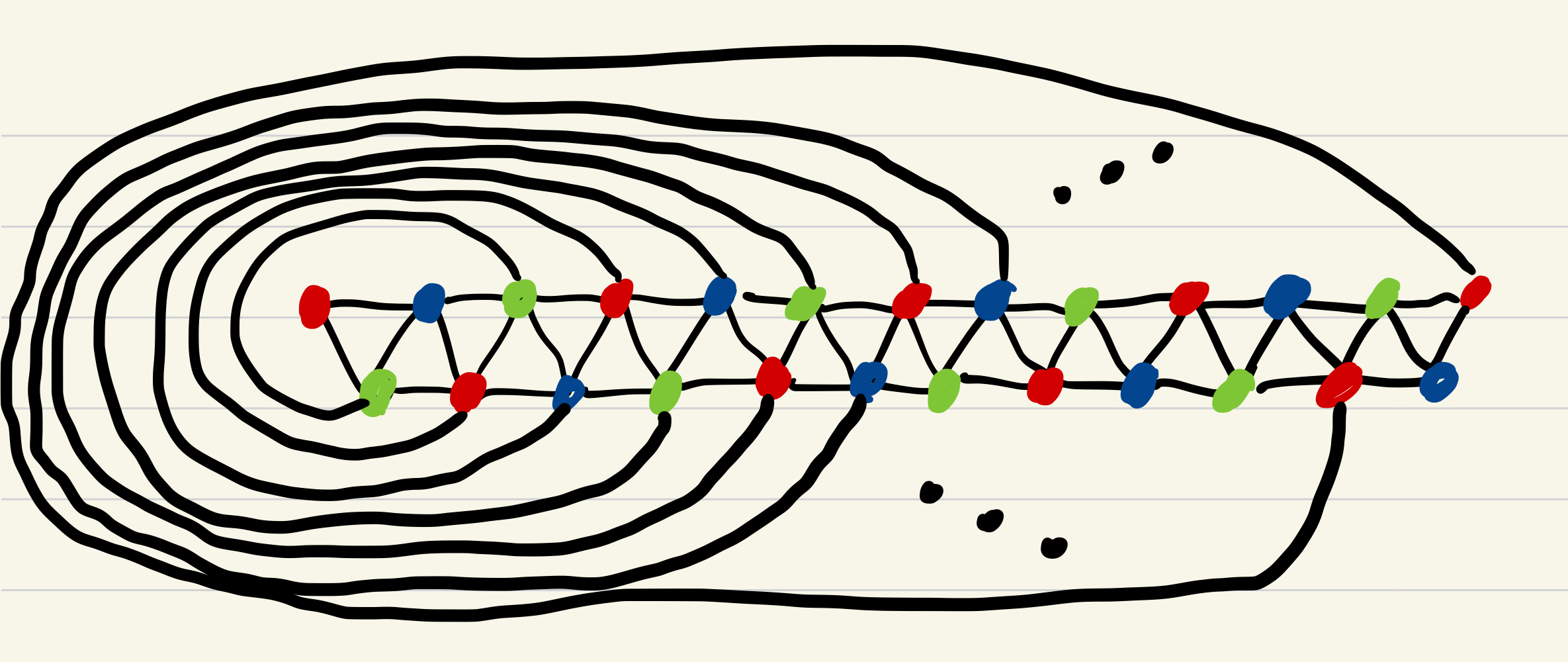

Even the special case of planar graphs without separating 3-cycles (which are contained in 4-connected triangulations) seems hard. In fact, for this special case the answer might be greater than $n/2$. The best lower bound I could come up with for general $n$ is $3n/5$. It comes from the fact that the graph in this picture has no independent set larger than $3n/10 + O(1)$.

Note that a version of the example above with separating triangles seems to give another $n/2$ upper bound on the size of the largest induced forest in a planar graph. This upper bound looks somewhat different from that of Akiyama and Watanabe and makes me doubt that tripod decompositions have much to offer for this problem. (If we break ties appropriately, then the Sperner triangle in this example has one edge on the outer face.)

There is some reason to believe that 4-connected triangulations might be different since 4-connected triangulations are Hamiltonian, meaning that their edge set is the union of two outerplanar graphs with a common dominant face. Any edge-maximal outerplanar graph $G$ has a unique 3-colouring, up to renaming of colours. This 3-colouring is also acyclic. To see why, observe that any cycle in $G$ contains an induced triangle that receives three distinct colours. Therefore the two largest colour classes induce a cycle-free graph of size at least $2n/3$. West’s page attributes this result to Hosono.