Layered Partitions/Product Structure

$\DeclareMathOperator{\lw}{lw}\DeclareMathOperator{\tw}{tw}\DeclareMathOperator{\pw}{pw}$Remember that a layered partition $(\mathcal{L},\mathcal{P})$ of a graph $G$ consists of a layering $\mathcal{L}$ of $V(G)$ and a partition $\mathcal{P}$ of $V(G)$. The layered width of the partition is defined as $\lw(\mathcal{L},\mathcal{P}):=\max\lbrace|L\cap P|:(L,P)\in\mathcal{L}\times\mathcal{P}\rbrace$. We are interested in layered partitions that have small layered width and in which the treewidth of the quotient graph $H:=G/\mathcal{P}$ is small.

It is easy to check that $G$ has a layered partition $(\mathcal{L},\mathcal{P})$ with $\lw(\mathcal{L},\mathcal{P})\le w$ if and only if $G$ is isomorphic to a subgraph of $H\boxtimes P\boxtimes K_w$, where $H:=G/\mathcal{P}$, $P$ is a path, and $K_w$ is a clique on $w$ vertices. The Planar Product Structure Theorem states that, for every planar graph $G$, there exists a planar graph $H$, $\tw(H)\le 8$, and a path $P$ such that $G\subseteq H\boxtimes P$. A second version of the theorem states that for every planar graph $G$ there exists a planar graph $H$, $\tw(H)\le 3$, and a path $P$ such that $G\subseteq H\boxtimes P\boxtimes K_3$.

We say that a graph family $\mathcal{G}$ has (treewidth/pathwidth) product structure if every member of $\mathcal{G}$ is isomorphic to a subgraph of a strong product of a bounded treewidth/pathwidth graph and a path.

Any graph with product structure has an $I$-shaped separator of order $O(\sqrt{n})$. This is a separator of the form \[ S\subseteq (V(H)\times \lbrace x, y\rbrace) \cup (K \times P_{x,y}) \] where $x$ and $y$ are two vertices of $P$, $K$ is a bag in width-$t$ tree-decomposition of $H$ and $P_{x,y}$ is the path from $x$ to $y$ in $P$. (This can be proven by starting at the median row $m$ of $G$. The vertices $x$ and $y$ are the closest vertices $x < m < y$ that define rows of size at most $\sqrt{n}$. The bag $K$ is just a balanced separator of the weighted treewidth-$t$ graph where the weight of a vertex $v$ is $|\lbrace(v,z)\in V(G):z\in V(P_{x,y})\rbrace |$. )

The planar product structure theorem has several generalizations and applications and there are a lot of open problems left and more applications to be found.

Other Product Structure Theorems

The product structure theorem generalizes to Euler genus-$g$ graphs. In this generalization, the graph $H$ is an apex graph and the layered width of the partition is $O(g)$. This can be generalized even further, all the way up to apex-minor free graphs, though the layered width is no longer explicitly bounded as a function of the forbidden minor.

The Structure of $k$-Planar graphs

Dujmović, Morin, and Wood showed that $k$-planar graphs have layered $H$-partition of layered width $O(k^2)$ where $H$ has treewidth $O(k^3)$. It would be nice to reduced the treewidth of $H$.

The Structure of Disk Graphs of Bounded Ply

A disk graph is a graph whose vertices are closed disks in $\R^2$ and that contains an edge $uv$ if and only if $u\cap v\neq\emptyset$. The ply of a disk graph is the maximum number of disks/vertices of $G$ that contain a single point. A unit disk graph is a disk graph whose vertices/disks all have the same radius.

The preceding conjecture is probably easy and so is its generalization to $d$ dimensions.

Update: The $\R^d$ version of the preceding conjecture is proven in the paper by Dvořák et al in Theorem 27. The same paper, in Open Problem 29, asks a question closely related to the following conjecture:

The following graph provides a counterexample. Let $Q$ to be a touching unit disk representation of a $n\times n$ grid. Add a set $A$ of $r\in \omega(1)$ disks to $Q$ that are pairwise disjoint but such that each disk intersects $r\in\omega(1)$ disks of $Q$. (We can easily do this for some $r\in\Omega(\sqrt{n})$.) The resulting disk graph $G$ has ply at most $3$ so, if the conjecture is true, then $G$ is a subgraph of $H\boxtimes P\boxtimes K_{f(3)}$ where $\tw(H)\le f(3)$. Furthermore, for each $a\in A$, $Q[N_G(a)]\subseteq G[N_G[a]]$ contains an $\Omega(r)\times \Omega(r)$ grid, so $\tw(G[N_G[a]]) \in \Omega(r)$.

If the conjecture is true, then there exists a homomorphism $\psi:G\to H\boxtimes P+K_{f(3)}$. The diameter of $G[N_G[a]]$ is at most $2$. Therefore, if $\psi$ maps all vertices of $N_G[a]$ to $H\boxtimes P$ then $\psi$ maps all vertices of $N_G[a]$ to $H\boxtimes P_3$ where $P_3$ is a subpath of $P$ containing at most $3$ vertices. Therefore \[ \Omega(r)\le \tw(G[N_G[a]])\le \tw(H\boxtimes P_3) \le 3\cdot \tw(H) \] so $\tw(H)\in \Omega(r)\subseteq \omega(1)$, which is a contradiction since $\tw(H)\le f(3)\in O(1)$. Therefore $\Psi$ must map some vertex of $N_G[a]$ to a vertex of $K_{f(3)}$. But this is true for each $a\in A$, so it must be the case that $f(3)=|V(K_{f(3)})|\ge |A|=r\in\omega(1)$, also a contradiction. ∎

The preceding argument actually shows something considerably stronger. Let $G_n$ denote the $n\times n + r$ vertex graph described above. For any integer $b$ and any bounded-degree graph $R$, there exists an $n$ such that $G_n\not\subseteq H\boxtimes R + K_b$. This includes the interesting case $R=P\boxtimes \cdots\boxtimes P$ where the number of factors in the product is a constant. The key observation is that $\psi$ must take $N_G[a]$ onto a subgraph of $H\boxtimes R + K_b$ of diameter at most $2$. The bounded degree of $R$ ensures that this subgraph either includes a vertex of $K_b$ or has bounded treewidth. (In particular, the treewidth is bounded by $\tw(H)\cdot(\Delta^2+\Delta+1)$.)

Open Problem 29 in this paper asks if every constant ply ball intersection graph in $\R^d$ can be expressed as clique-sums on graphs of the form $H\boxtimes R+K_b$. I think the graph $G$ described above shows that the answer is no, but I first have to convince myself that clique-sums don’t help to decompose $G$.

One might think of fixing the conjecture by restricting it to bounded-degree disk graphs. That might work for disk graphs, but it won’t work for ball intersection graphs in $\R^3$. In $\R^3$ we can replace each vertex $a\in A$ with a complete binary tree $T_a$. This gives a graph of maximum degree $5$ and ply $2$ and $\psi$ has to map $N_G[T_a]$ onto a subgraph of diameter $O(\log r)$. By taking $r\in \Omega(\sqrt{n})$, the proof for $H\boxtimes P+K_{f(s)}$ finishes with $f(2)\in\Omega(\sqrt{n}/\log n)$. The version for $H\boxtimes R+K_r$ finishes with $f(2)\ge \sqrt{n}/g(O(\log n))$ where $g$ is the growth function of $R$ (so $g(x)$ is the size of the largest ball of radius $x$ in $R$). This disproves the conjecture when $g(x)\le 2^{o(x)}$. In particular, it disproves the conjecture when $R$ has polynomial growth, which by the result of Krauthgamer and Lee, is equivalent to $R\subseteq P\boxtimes\cdots\boxtimes P$.

Another Try at Characterizing Bound-Ply Disk Intersection Graphs

Consider a graph $G\subseteq G_0,\ldots,G_c$ that can be constructed in the following way:

- For each $i\in\lbrace 0,\ldots,c\rbrace$ Begin with graphs $G_i:=H_i\boxtimes P$ for some graph $H_i$ of treewidth at most $t$ and some path $P$.

- For each $0\le i < j\le c$ add edges from $G_j$ to $G_i$ that satisfy the following constraints:

- For each $0 \le i < j\le c$, there exists a separation $(A,B)$ of $G_i$ having order $|A\cap B|\in O(\sqrt{|G_i|})$ such that $|N_G(A\setminus B)\cap V(G_j)|\le \max\lbrace c, 2|G_j|/3 \rbrace$ and $|N_G(B\setminus A)\cap V(G_j)|\le \max\lbrace c, 2|G_j|/3 \rbrace$ . (And maybe something similar for subgraphs of $G_i$.)

If the ratio between the largest disk and smallest disk is bounded by $\sigma$ then the preceding conjecture probably holds with $c=O(\log\sigma)$. To see this, partition the disks into $c=O(\log\sigma)$ sets $D_0,\ldots,D_c$ where the radii of disks in $D_i$ differ by a factor of at most $2$. Let $G_i$ be the intersection graph of $D_i$. Then, by the result on unit disk graphs discussed above, $G_i\subseteq K\boxtimes P\boxtimes P$ for some clique $K$ of size $O(c)$. For any graph $v\in V(G_j)$, $N_G(v)\cap V(G_i)$ is contained in a square subgrid of $G_i$. Now, showing the necessary separation property involves showing that an $n$-vertex subgraph of $P\boxtimes P$ whose vertices are covered by squares of ply $O(c)$ has an $O(\sqrt{n})$ separator of the covering squares. We can do this with $I$-shaped separator. In fact, this separator will even guarantee that $|N_G(A)\cap V(G_j)| \le 2|G_j|/3 + O(\sqrt{|G_i|})$.

Of course, this partitioning of disks based on radii will, in general result in too many parts. The next section looks at an alternative that might be the right thing to use for the graphs $G_1,\ldots,G_c$.

Well-Spaced Sets of Disks

We say that a set $D$ of disks is well-spaced if no disk in $D$ contains the center of any other disk in $D$.

Lemma D: For any set $D$ of well-spaced set of disks and any point $p\in R^2$, there are at most $6$ points disks in $D$ that contain $p$.

Proof: Let $c_1,\ldots,c_k$ be the centers of these disks in $D$ that contain $p$. A standard argument (used, for example to bound the maximum degree in a Euclidean minimum spanning tree) shows that $\angle c_i p c_j\ge \pi/3$ for each $i\neq j$. Therefore $k \le 2\pi/(\pi/3)=6$. □

Conjecture: Let $G$ be the intersection graph of a set $D$ of well-spaced disks. Then $G\subseteq H\boxtimes P$ for some bounded treewidth graph $H$ and some path $P$.

My gut says that this conjecture has a proof similar to the proof for $k$-planar graphs. The main objects we’re interested in are vertical paths in the BFS tree of $G$. Each such path corresponds to a polygonal curve through the centers of the corresponding disks. This curve may intersect other disks not on the path, so a leg of the tripod becomes the set of all disks intersected by one of these paths. This is similar to what happens with k-planar graphs, where a tripod leg starts with a vertical path in the BFS tree of the planar graph obtained by adding a dummy vertex at each crossing. When a leg contains such a dummy vertex we add the four endpoints of corresponding pair of crossing edges to the leg. (This may put a vertex in more than one leg, but we resolve this by storing the vertex at the first leg where this happens.)

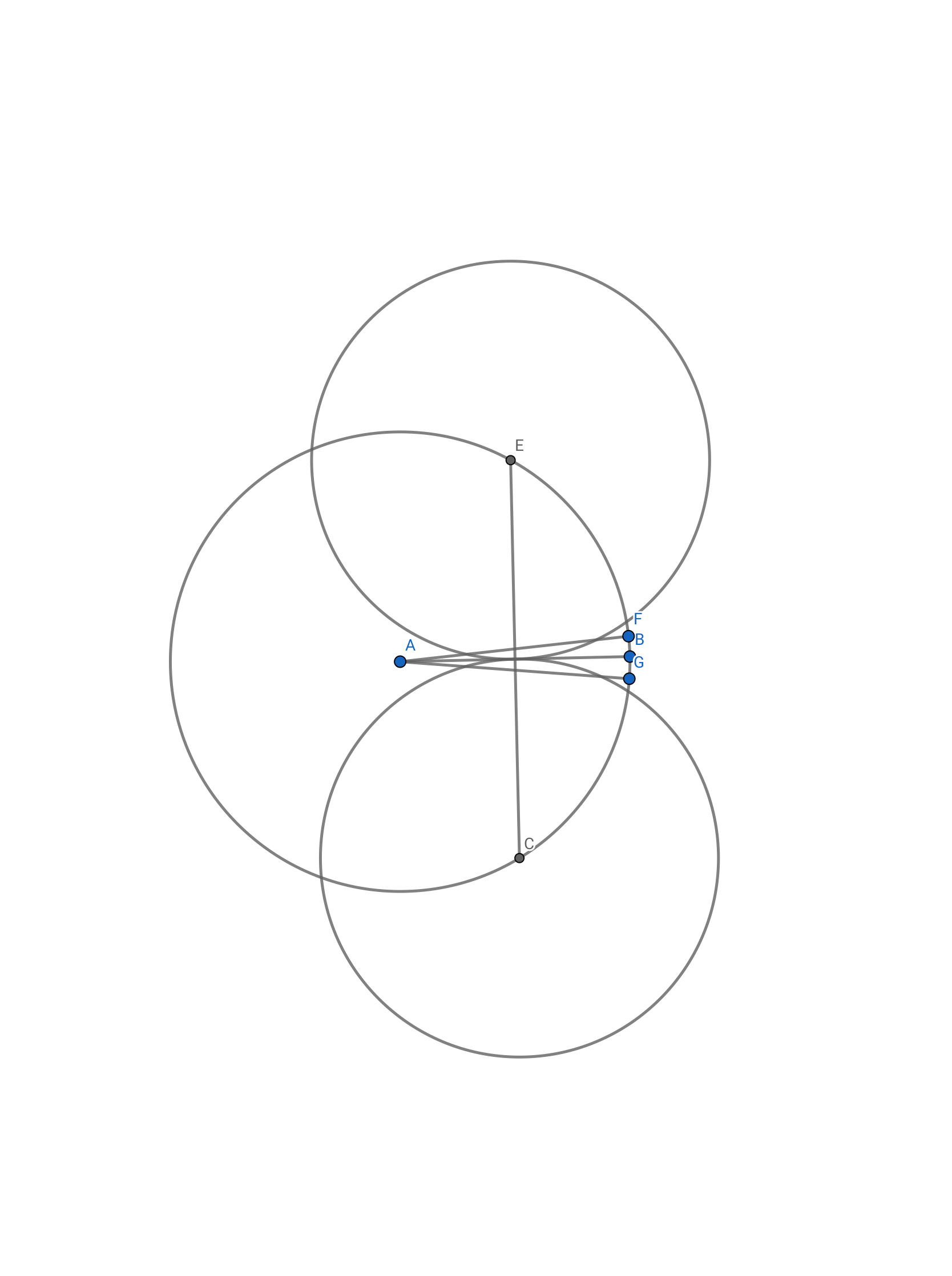

As it turns out, the graph drawing we get by drawing each vertex the center of its corresponding disk and drawing the edges with straight lines is not $k$-plane for any fixed $k$. The figure below illustrates why this is so. In this figure, the edge $EC$ is crossed by a large number of edges $AF$, $AB$, $AG$. The disks $F$, $B$ and $G$ have radius $\epsilon$ for some tiny $\epsilon > 0$.

In the $k$-planar setting, we use the Pillipczuk-Siebertz $k$-reachability lemma to upper bound the treewidth of the graph $H$ we obtain by contracting legs. This uses $k$-planarity, so we’ll need to do something different, that uses the geometry. There is certainly a lot of structure in the crossings that occur in this drawing. In particular, I believe that the number of independent edges that cross a particular edge $uv$ is $O(1)$, so the set of edges that cross $uv$ has an $O(1)$-sized vertex cover. (I also suspect that no pair of highly-crossed edges crosses each other.)

The Structure of $k$-nearest neighbour graphs in $\R^d$

Here’s one from David Wood:

The conjecture is true for $d=1$ (easy) and $d=2$ (in our paper on the structure of $k$-planar graphs). Note that any complete binary tree is a $k$-nearest neighbour graph of a point set in $\R^2$, so the result of Krauthgamer and Lee on graphs with polynomial growth doesn’t apply.

Here’s a stronger version that has more of a “universal graphs” flavour:

In addition to being a consequence of the Krauthgamer and Lee result, the case $d=1$ is easy: If the points are $x_1<x_2<\cdots<x_n$, then consider the graph that contains the edges $x_{i+r}x_i$ for each $r\in\lbrace-k,\ldots,k\rbrace$ and each $i\in\lbrace 1,\ldots,n\rbrace$. This graph contains the $k$-nearest neighbour graph and has bandwidth $O(k)$. Having bandwidth $O(k)$ is equivalent to being a subgraph of $K_{O(k)}\boxtimes P$. (David Wood pointed out the connection between $K_x\boxtimes P$ and bandwidth.)

The second conjecture is still open for all $d\ge 2$. The argument for $d=1$ has a Yao graph flavour to it, which suggests we may be able to show that for every $k$-nearest neighbour graph $G$ of points in $\R^d$, $G\subseteq K_{f(k,d)}\boxtimes P^{f(k,d)}$.

The second conjecture is not true, even when $d=2$ and $k=1$. $K\subseteq P^{|K|}$, so $K\boxtimes P^{d}\subseteq P^{d+|K|}$. The complete binary tree of height $h$ is a $1$-nearest neighbour graph of points in $\R^2$. The growth rate of $K\boxtimes P^d$ is $r^{O(d)}$, but the growth rate of a complete binary tree is $2^{\Theta(r)}$. The Krauthgamer and Lee result really does characterize subgraphs of $P^d$ (and hence $K\boxtimes P^d$) in terms of polynomial growth rate. The main distinction is that some classes of dimension $\sigma$ (e.g., minor-closed) are subgraphs of $P^{O(\sigma)}$ while the general result only shows that they are subgraphs of $P^{O(\sigma\log\sigma)}$.

[Stream of consciousness…] So a graph is a subgraph of $H\boxtimes P^d$ if it consists of many copies of a bounded treewidth part, $H$, that are interconnected in a bounded growth network, $P^d$.

The structure of $k$-quasiplanar graphs

A topological graph is $k$-quasiplanar if it contains no $k$-tuple of pairwise crossing edges. An old conjecture states that, for every $k$, there exists a constant $c_k$ such that every $n$-vertex $k$-quasiplanar graph has at most $c_k n$ edges. This is known to be true for $k\in\lbrace 3, 4\rbrace$. (See Suk for the $k=4$ case and Ackerman and Tardos for a nice proof of the $k=3$ case.)

We can’t hope to have a product structure theorem even for $3$-quasiplanar graphs because a grid plus an apex vertex has diameter 2, treewidth $\Omega(\sqrt{n})$ and is 3-quasiplanar. Still, I would like to know if some of the applications like queue-number and non-repetitive colouring still work for 3-quasiplanar. The idea would be to identify a set of exceptional vertices that we can remove to get an $f(k)$-planar graph, solve the problem on the planar graph and then deal with these exceptional vertices separately.

Update (from David Wood): 3-quasiplanar graphs include all thickness 2 graphs, which include 1-subdivisions of all complete graphs. So 3-quasiplanar graphs have unbounded queue-number and unbounded nonrepetitive chromatic number. In the language of Nesetril and Ossona de Mendez, they are somewhere dense. This is part of the reason why the conjecture that k-quasiplanar graphs have bounded average degree is so hard.

In light of the preceding update, this seems like a fruitless pursuit. Also, the disk intersection graph G described here is $3$-quasiplanar. (It probably has unbounded queue number.)

The structure of graphs with (hereditary) linear crossing numbers

$\DeclareMathOperator{\cr}{cr}$ For a drawing $\Gamma(G)$ of a graph $G$, let $\cr(\Gamma(G))$ denote the number of crossings in the drawing $\Gamma$. (The number of triples $(e_1,e_2,p)\in E(G)\times E(G)\times\R^2$ such that the drawing of $e_1$ and $e_2$ each contain the point $p$.) Call a graph drawing $G$ $c$-good if, for every $S\subseteq V(G)$, $\cr(\Gamma(G[S]))\le c\cdot|S|$. Say that $G$ is $c$-good if there exists a $c$-good drawing of $G$.

I thought we could weaken this conjecture to drawings with the following property: Each crossing $(e_1,e_2,p)$ can be charged to one of $e_1$ or $e_2$ in such a way that each edge of $G$ is assigned at most $k$ crossings. However, David Wood points out that the ability to direct crossings in this way already has a name: $k$-gap planarity, and is equivalent to the statement ``every subgraph of the crossing graph has degree at most $2k$.’’ So this version is equivalent (up to a factor of 2) to the definition of $k$-good. This is all explained in Footnote 6 in this paper.

The structure of sparse hereditary graph families

The planar product structure theorem is evidence for this conjecture, since planarity is preserved when taking subgraphs and there are only $n!2^{O(n)}$ $n$-vertex planar graphs.

Note: Labelled graphs may not be the right thing to count here. Perhaps unlabelled graphs would be more appropriate.

This is closely related to the implicit graph conjecture. The main difference is that we consider a family of graphs that is closed under taking subgraphs, not just induced subgraphs. This, combined with upper bound on the number of $n$-vertex graphs implies that $n$-vertex graphs in the family have $O(n)$ edges. Of course, this is a necessary condition for $G$ to be a subgraph of $H\boxtimes P$ since any $n$-vertex subgraph of $H\boxtimes P$ has only $O(n)$ edges.

Update: David Wood points out that the class of apex graphs is closed under taking subgraphs, has the right number of $n$-vertex members. It also has no product structure theorem because it contains diameter-$2$ treewidth-$\Omega(\sqrt{n})$ graphs, so it’s a counterexample.

The structure of outerplanar graphs

We can prove a baby product structure theorem for outerplanar graphs. For a rooted ordered tree $T$, let $T^+$ be the graph obtained from $T$ by adding, for each node $v$ of $T$ a path that contains the children of $v$ in order. Then, for every outerplanar graph $G$, there exists a tree $T$ such that $G$ is a subgraph of $T^+\boxtimes K_2$. So $G$ is contained in the strong product of a graph tree-like thing and a single edge.

Update (Feb 2021): I don’t think the preceding paragraph is correct.

I don’t know of any applications of this result, but there must be some that generalize results for trees to outerplanar graphs. A good first problem to consider is nonrepetitive colouring of outerplanar graphs. The best bound is $12=4\times 3$ where the $3$ comes from non-repetitively colouring each BFS layer (a set of disjoint paths) and $4$ comes from a nonrepetitive palindrome-free colouring of the BFS layers themselves.

Another possibility to consider is anagram-free colouring. David and a student showed that every tree $T$ has an anagram-free colouring using at most $4\pw(T)$ colours. Can we extend this to show that every outerplanar graph $G$ has an anagram-free colouring using $O(\pw(G))$ colours? Probably not, because even $P\boxtimes K_2$ does not have bounded anagraph-free chromatic number (Carmi, Dujmović, Morin).

The structure of trees and $t$-trees

Is it true that every $n$-vertex tree $T$ is a subgraph of $H\boxtimes P$ where $\pw(H)\in O(\log n/\log\log n)$ and $P$ is a path?

Is it true that every $n$-vertex $t$-tree $G$ is a subgraph of $H\boxtimes P$ where $\pw(H)\in O(\log n/\log^{(t+1)} n)$?

These two questions are motivated by our work vertex-ranking.

Update: The answer is no. If $T$ is a complete binary tree of height $h$ and $T$ is a subgraph of $H\boxtimes P$, then $H$ contains a subdivision of a complete binary tree of height $\Omega(h)$. It’s a boring packing argument that projects $T$ onto $H$ and starts with: “Consider the $2^c$ depth $c$ nodes of $T$. They project onto at least $2^c/c$ distinct nodes of $H$ and if $2^c/c \ge 3$, then at least one of those nodes is different from the projection of the root of $T$ onto $H$.” So $H$ contains at least:

- the projection of the root of $T$

- 2 paths of length at most c from the root to two distinct nodes.

And now continue like that while working out boring details….

Layered Partitions versus Layered Decompositions

Update: We explored this topic and wrote a paper about it.